1 TOPOLOGY

The term topology in the geography of a place is the study of the relations associated with the position of a political unit on the globe, such as a country or a state. It examines, among other aspects, the antipodes, the parallels and meridians that cross the territory (especially the main ones along its extent), the climatic zones of the region, its extreme points, time zones, and the distances between these elements and its neighboring areas.

Situated entirely in the Western Hemisphere, the three latitudinal extremes (west, mainland east, over east) of the country are west Greenwich. Crossed by the Equator and the Tropic of Capricorn, the northern end of the country is in the Northern Hemisphere, and the southern end is in the southern temperate region. Brazil is the longest country in the world, spanning 4,395 km from north to south, and the only country in the world that has the equator and a tropical line (Tropic of Capricorn) running through it. For many curiosities for Brazilian territory, see Lista de Extremos do Brasil (Wikipedia).

EXTREMES

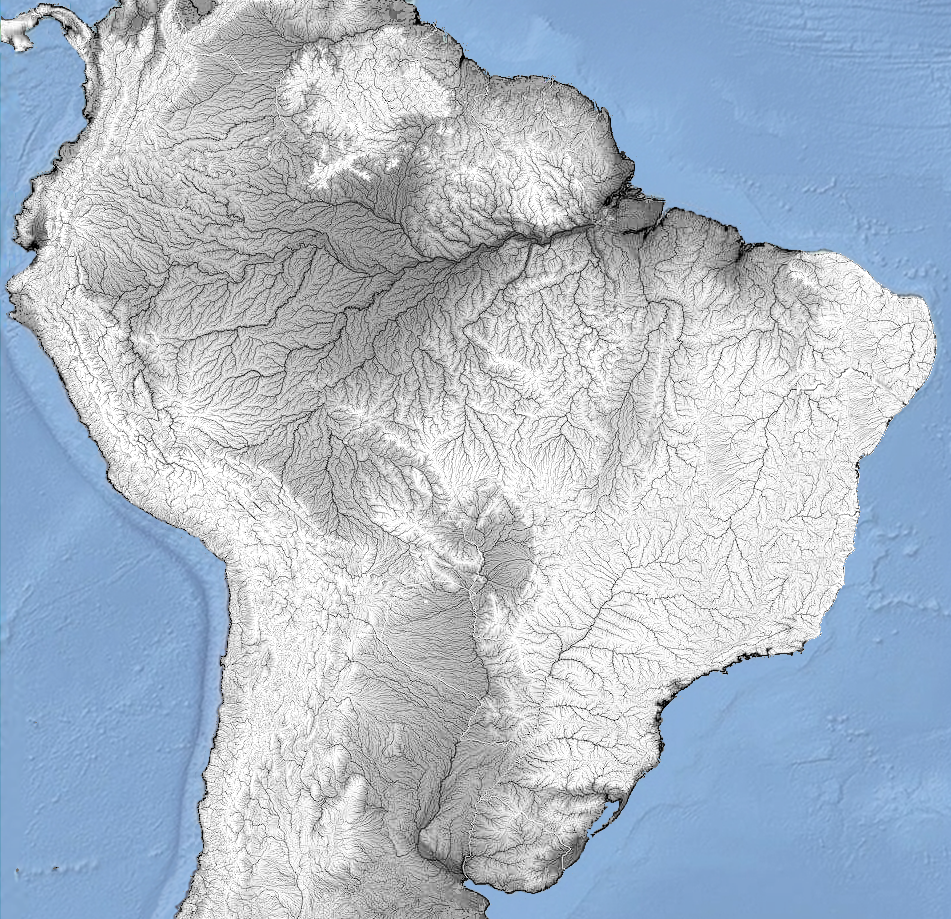

The distances of the latitudinal and longitudinal extremes are almost equivalent, with a difference of only 53 km, less than 2% of both (4,379 km N/S, 4,323 km E/W). Interestingly, the continental E and W extremes are almost at the same latitude (0º22'48'' difference), which makes the segment that connects them almost coincident with the largest parallel in the national territory (approx. 7º21' S) and also the longest 'straight' line inside Brazilian territory. The longest meridian in the national territory (approx. 53º29' W) is approximately 3,832 km long and is quite distinct from the segment that joins the N and S extremes.

N: Monte Caburaí, Roraima (RR | 05°16′10″ N). For details of an expedition to this point (Amazonas Abenteuer). Brazil’s northernmost point is the 10th southernmost among all extreme-north points located in the Northern Hemisphere.

E (continental): Ponta do Seixas, Paraíba state (PB; 34°47′34″ W). The easternmost continental point of Brazil is the 14th easternmost among countries whose extreme-east point lies west of Greenwich (Wikipedia), and it is the easternmost point in the Americas.

E (insular): Ilha do Sul, Martim Vaz Archipelago, Espírito Santo state (ES; 28°50′51″ W).

S: Arroio Chuí, Rio Grande do Sul state (RS; 33°45′03″ S). Brazil’s southernmost point ranks as the 7th most southerly among sovereign states (Wikipedia).

W: Serra do Divisor, Acre state (AC; 73°58′59″ W). Brazil’s westernmost point is the 23rd most westerly among all sovereign states (Wikipedia).

ZONES

The portion of Brazil lying in the northern Hemisphere covers an area of 601,427 km² (7.062% of the national territory), based on manual measurements performed for this study using the Google Earth Polygon tool. This area spans parts of the states of Amazonas (140,600 km² in the western segment and 3,960 km² in the eastern segment), Roraima (201,347 km²), Pará (128,234 km²), and Amapá (127,286 km²).

Using the same methodology, the temperate zone covers a very similar area — 600,935 km² (7.056% of Brazil’s territory) — distributed across portions of São Paulo (48,319 km²), Mato Grosso do Sul (8,250 km²), and Paraná (167,272 km²), as well as the entirety of the states of Santa Catarina (95,346 km²) and Rio Grande do Sul (281,748 km²).

POLE OF INACESSIBILITY

In South America, the continental Pole of Inaccessibility is located in central Brazil, at 14.05°S, 56.85°W, near the municipality of Arenápolis, Mato Grosso state, approximately 1,504 km from the nearest coastline (Castellanos & Lombardo, Scottish Geographical Journal, 2007 | Wikipedia). In May–June 2023, the precise point was reached by British explorer Chris Brown, who reportedly found a machete lying exactly at the location (Brown Site).

BRAZILIAN EXTREMES IN MAINLAND, LENGHTS OF IMPORTANT LINES, ZONES, AND OTHER REMARKABLE POINTS

ANTIPODES

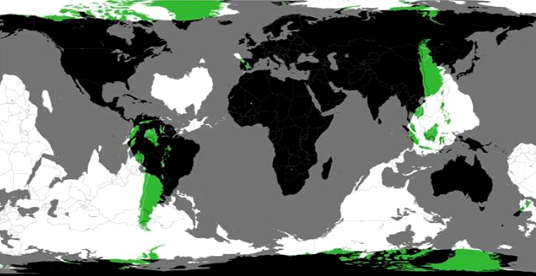

Most regions of the world do not have land-based antipodes. Exceptions include parts of South America, East and Southeast Asia, Antarctica, the Arctic, the Iberian Peninsula, and New Zealand. Much of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, Greenland, and a portion of Siberia lie opposite Antarctica, including the Antarctic Peninsula. A very large area of China is antipodal to Argentina and Chile; Peru is antipodal to Indochina; Ecuador is antipodal to Peninsular Malaysia; and Colombia is antipodal to Sumatra.

In Brazil, parts of Sulawesi lie opposite Guyana and the state of Pará in northern Brazil, while Borneo and the Philippines have antipodes in Brazil across the states of Mato Grosso, Pará, Roraima, and Amazonas.

DISTANCES

The northernmost point of Brazil is closer to Canada, in the direction of Nova Scotia, than to Brazil’s southernmost points (4,262 km ✕ 4,379 km). Rio Grande do Norte is closer to Africa, in the direction of Guinea-Bissau (2,768 km), than to cities such as Curitiba or Florianópolis.

TIME ZONES

Brazil has four time zones. The first is UTC-2, which includes only a few Brazilian islands, most notably Fernando de Noronha. The second time zone is UTC-3, covering most of the country, including the capital, Brasília. It encompasses the NE, SE, and S regions, as well as parts of the N and WC regions, and is the country’s official time zone. The third time zone is UTC-4, one hour behind Brasília, including parts of the North (RR, RO, and part of AM) and Center-West (MS, MT) regions. The fourth and last time zone is UTC-5, two hours behind Brasília, covering only the state of Acre and a small portion of Amazonas (Mundo Educação).

Worldwide, countries with four or more time zones include France (12), Russia (11), USA (11), Australia (9), UK (9), Canada (6), Denmark (5), New Zealand (5), Brazil (4 — 9th), and Mexico (4). However, when considering only the time zones of the contiguous territory, the list includes Russia (11), the USA (6), Australia (5), Canada (6), Brazil (4 - 5th), and Mexico (4), these tied (Wikipedia).

LINES IN SEA

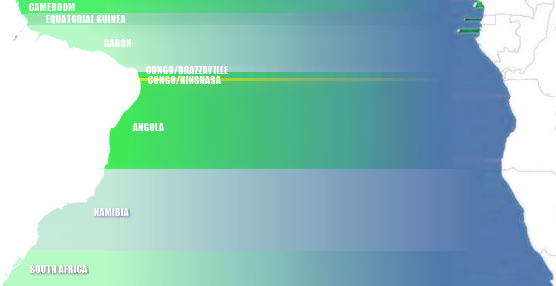

Facing at the Brazilian coastline and projecting eastward toward Africa, the state of Amapá is generally aligned with Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea. From Amapá to Rio Grande do Norte, most of the littoral is positioned opposite Gabon, aside from a limited segment that corresponds to the Republic of the Congo. A small coastal section of Rio Grande do Norte lies opposite the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The shoreline extending from Rio Grande do Norte to Bahia aligns primarily with Angola, while the sector between Bahia and Santa Catarina corresponds to Namibia. Finally, the stretch from Santa Catarina to Chuí is broadly aligned with the coast of South Africa.

FACING MAPS BETWEEN SOUTH AMERICA AND AFRICA; FOR ALL COLECCTION, SEE RELATIVELY INTERESTING

2 SPACE

Due to its geographical location, Brazil holds one of the most privileged positions on the planet for rocket launches, offering several advantages. The primary one is that the Earth's rotational speed near the Equator boosts the propulsion of launch vehicles, significantly reducing the consumption of propellant fuel and cutting costs by up to 30%. This is also because the Earth is an oblate spheroid (that is, flattened at the poles), which means the Equator lies closer to space and farther from the Earth's center, reducing both the travel distance and the gravitational force that must be overcome to launch an object. The Alcântara Launch Center (CLA), one of the country's two spaceports, is located in the state of Maranhão, near the town of Alcântara, in the northern part of the state (Tecmundo/2023).

The South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA) is a striking irregularity in Earth’s magnetic field, characterized by a significant reduction in field strength over a vast region spanning the South Atlantic Ocean, from South America to southern Africa. This anomaly, where the magnetic field intensity drops to approximately one-third of the global average, affects low-Earth orbit satellites, spacecraft, and scientific research, offering a unique lens into the planet’s geomagnetic dynamics. For life on Earth’s surface, the SAA has negligible direct effects. The atmosphere, with a mass equivalent to a 10-meter-thick water layer, effectively shields against cosmic and solar radiation, even in the SAA’s weaker magnetic zone. Populations in affected regions, such as Brazil, Argentina, and South Africa, experience no measurable health risks, as radiation levels remain within safe limits at sea level. The anomaly’s influence is confined to higher altitudes, where atmospheric density decreases, posing no threat to ground-dwelling organisms (News Space Economy).

The Curuçá River Event was an impact event that occurred in the Brazilian state of Amazonas on August 13, 1930, similar to the Tunguska event that took place in Siberia in 1908. The event was likely caused by a cosmic body falling in the region of the Curuçá River, in the municipality of Atalaia do Norte, Amazonas. At the time, local riverine communities and Indigenous people reported seeing 'fireballs' falling from the sky over the right bank of the Curuçá River (Wikipedia).

The Bendegó is the largest known Brazilian meteorite to date. It weighs 5.36 tons and measures 2.15 m ✕ 1.5 m ✕ 65 cm. With a somewhat flattened shape, it resembles a riding saddle. It is a compact mass composed mainly of iron and nickel, with smaller amounts of other elements. Despite its colossal size, it no longer ranks among the ten largest meteorites in the world (16th today), although it was the second largest in weight and size at the time of its discovery. It was found in the interior of Bahia (in the region where the municipalities of Monte Santo and Uauá are located today) and is now housed in the meteorite hall of the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro (Meteoríticas | Carvalho, W.P. et al., Revista Brasileira de Geociências, 2011).

3 ATLANTIC BRAZIL

The Brazilian coastline extends for 7,491 km, making it the 15th longest national coastline in the world (Wikipedia). Approximately 8.15% of it lies in the Northern Hemisphere, while the remaining 91.85% stretches across the Southern Hemisphere, spanning 17 states. The entire coast borders the Atlantic Ocean. The coastal region features a diverse array of geographical formations, including islands, bays, tropical beaches interspersed with mangroves, lagoons, tidal flats, dunes, and extensive coral reefs. For the most comprehensive reference on Brazil’s coastal zones, consult the Atlas Geográfico das Zonas Costeiras e Oceânicas do Brasil (IBGE, 2011).

EEZ

Brazil’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) is an offshore area covering 3.6 M km² along the Brazilian coast, making it the 11th largest in the world. The Northeast region contains the largest portion of Brazil’s EEZ due to several widely spaced islands forming a continuous marine zone. However, Trindade Island lies too far from the coast to be included in a similar configuration (Wikipedia).

On March 26, 2025, the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) of the United Nations (UN) approved a proposal submitted by Brazil to extend its continental shelf — the submerged prolongation of its land territory — off the northern coast. This initiative, led by the Brazilian Navy with support from Petrobras (the main financial backer), grants Brazil exclusive rights to explore a maritime area of 360,000 km², equivalent to the size of Germany, located beyond the 200-nautical-mile limit off the coasts of Amapá and Pará (Poder Naval | Defesa em Foco). To secure this extension beyond 200 nautical miles, Brazil had to provide technical evidence demonstrating that the underwater relief of the Equatorial Margin is a natural extension of its continental landmass. The CLCS requires geological proof that confirms the physical continuity between the continent and the seabed. The submission process involved a series of technical reports and diplomatic negotiations, which began back in 2004. The initial request was denied but resubmitted in 2007 based on new data. In February of this year, members of the Brazilian Continental Shelf Survey Plan (LEPLAC) joined the Brazilian Delegation at the 63rd Session of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) in New York (USA). On that occasion, the analysis of the submission concerning the Equatorial Margin was concluded, and the review of the Eastern and Southern Margins was initiated. This decision is the result of seven years of interaction between Brazilian experts and CLCS specialists, marking a milestone in the definition of Brazil’s maritime boundaries. The UN had already recognized another extension of Brazil’s continental shelf in the southern region back in 2019.

COAST SECTIONS

The interaction of the geological background, sea level history, sediment supply, present climate (temperature, wind speed and precipitation) and associated oceanographic processes (waves and coastal currents) has contributed to the development of the different landscapes along the Brazilian coastline. There is a great variety of environments such as macrotidal plains covered by mangrove forests in the north; semi-arid coasts (bordered by Tertiary cliffs and delta-like coastal plains on the central coast); and wave-dominated environments in the south (either characterized by dissipative beaches at the border of the Late Quaternary coastal plain or rocky shores and eventually interrupted by reflective-to-intermediate pocket beaches). Based on these relatively unique characteristics, the major coastal typologies or compartments present in Brazil have been described includes six sections (Copertino, MS et al, Brazilian Journal of Oceanography, 2016).

The northern coast (1,200 km long), which begins at Cabo Orange in Amapá, receives the largest volume of sediment on the entire coast of Brazil because of the Amazon River and other associated rivers (e.g., Tocantins and Parnaíba). It has a wide continental shelf (up to 300 km wide) and is controlled by macrotidal processes (> 4 m, up to 6.3 within estuaries), with wide estuary mouths and short and narrow barriers. The region holds the largest mangrove system in the world and the gorge of the largest river in length, water and sediment discharge, the Amazon River. It has a tide-mud-dominated coast to the west (between Marajó Bay (PA) and São José Bay (MA), with 7,591 km² and 56.6% of all mangroves in country, Tomaz et al., Revista Brasileira de Climatologia, 2019 | W.R. Nascimento Jr. et al., Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 2012) and a tide-dominated mangrove coast to the east (Pará-Maranhão). This region includes the area with the highest tides in Brazil (São Marcos Bay, Maranhão state, up to 7m, Baías do Brasil | Czizeweski, Dissertation, 2019), the most remarkable of all Brazilian river deltas (delta of Parnaíba river, Feldens et al., Geo-Marine Letters, 2014), and several dune fields — among them the Lençóis Maranhenses, the largest dune system in the country and one of the most remarkable on the planet (ICMBIO).

The notheastern coast is a sediment-starved coastal zone, resulting from low relief, small drainage basins and a semiarid climate. The coast is dominated by sedimentary cliffs (Barreiras group), the river runoff is extremely low and the whole area suffers from coastal erosion. The coastline is characterized by the presence of actively retreating cliffs, beachrocks (cemented upper shoreface sediments) and coral-algal reefs built on top of the beach rocks and abrasion terraces. The northwestern section of the region is a semi-arid coast (Piauí, Ceará and the west coast of Rio Grande do Norte), very dry and highly impacted by erosion. The eastern section of the northeast coast, from south of Rio Grande do Norte to northern Bahia, has a more humid climate. It includes a barrier reef coast that stretches intermittently for 3,000 km (between Pernambuco and Bahia States) and comprises coral and sandstone barrier reefs that act like breakwaters, decreasing the wave energy and limiting sediment re-suspension to the shore.

The eastern coast (in Bahia, Espírito Santo and Rio de Janeiro) receives a considerable volume of sediment as a result of the presence of large rivers draining high-relief, humid areas. The presence of the sedimentary cliffs is still dominant but less continuous in the southern part. The region is marked by alternations in dominance between the waves generated by the trade winds and the swell waves generated by cold fronts from the south, and it is highly susceptible to the changes in dominance between tropical and subtropical climatic-oceanographic processes. The coast alternates among regions of equilibrium, accretion and erosion, with more than 30% of the coastal area suffering from erosion, and accretion occurring mainly on the coastal plains of the river delta. In this region lies the longest continuous stretch of coastal cliffs in Brazil, located in the municipality of Mucuri, in SE Bahia (Brazil in Line/Singularities).

The southerastern coast, along the Rio de Janeiro State coast, has an almost east-west alignment to the coastline, being highly exposed to storm waves from the south. The longshore sediment transport tends to be in equilibrium throughout the year, with the less frequent, high-energy waves (swell) from the south and southwest being compensated for by the more frequent waves from the southeast. In this region occurs the most pronounced of Brazil’s three upwelling zones, along the coast of Rio de Janeiro (Kaempf & Chapman, BOOK, 2016), off Cabo Frio (20°S–24°S).

The southeast/south rocky coast from the Ilha Grande Bay (Rio de Janeiro State) to the Santa Marta Cape (Santa Catarina State) is characterized by the proximity of the coastal mountain range (Serra do Mar), resulting in a submerged landscape with a sequence of high cliffs, innumerous small coves and beaches interconnected by rocky shores. From São Vicente to northern Santa Catarina, including the coast of Paraná, the coastline is formed by long beaches and wide coastal plains with wide estuaries, such as at Santos and Cananéia in São Paulo, Paranaguá and Guaratuba in Paraná and São Francisco do Sul in Santa Catarina. From northern Santa Catarina to southern Santa Catarina Island (the largest fully isolated island in Brazil, sufficiently distinct from the mainland in its contour, with 424.4 km², Brazil in Line/Singularities), the coastline becomes irregular with outcrops of the crystalline basement and small coastal plains.

The southern coast, from Santa Marta Cape (Santa Catarina) to Chuí (Rio Grande do Sul) on the border between Brazil and Uruguay, the coastline is formed by a long, wide, fine-grained and continuous beach in front of a multiple barrier-lagoon system, the widest lagoons being the Laguna dos Patos (largest coastal lagoon in South America and Brazil, covering an area of 10,100 km², separated from the Atlantic Ocean by a sandbar about 5 miles, Wikipedia) and Mirim Lake. The series of barriers are separated by low-lying areas occupied by freshwater wetlands and large fresh-water bodies, with no access to the sea but for the Rio Grande, Tramandaí and Chuy inlets. This is the longest barrier system in South America and certainly one of the longest in the world. It is in this area that the longest beach in the world is located (Praia do Cassino beach, 240 km, Statista | Travel2next). In this section of the coastline, in northern Rio Grande do Sul, stands the Torres Cliff, the highest cliffs in Brazil (48m high, Torres Website).

OCEANCIC ISLANDS

SALINITY AROUND SOUTH AMERICA

Regarding biodiversity on these islands, Atol das Rocas hosts 18 spp. of insects and 7 of arachnids (Almeida C.E. et al., Rev. Bras. Biol., 2000). Fernando de Noronha is home to three endemic land snail species (Salvador et al., Tentacle, 2022) and 453 insect species across 21 orders, primarily Diptera and Coleoptera (Rafael et al., Revista Brasileira de Entomologia, 2020). The Noronha worm lizard (Amphisbaena ridleyi Boulenger, 1890) is a reptile closely related to Caribbean species of the same genus (Graboski et al., Molecular Phylogenetic and Evolution, 2019). For data on Collembola in Brazilian islands, Lima et al. (Insects, 2021) provide information on Poduromorpha, while Lima et al. (Diversity, 2021) focus on Entomobryomorpha. In terms of bryophytes, Fernando de Noronha has (14:14/)31 spp. (Fieldguides, 2021), while Trindade hosts 38 spp., including 20 liverworts, 17 mosses, and one hornwort (Fieldguides, 2022).

BEACHES

There is no official catalog of the number of beaches in Brazil. The Guia 4 Rodas, a popular Brazilian travel and automotive magazine, listed 2,095 beaches in its 2007 edition (Mar Sem Fim). Among these beaches, two stand out in Brazil: Praia do Cassino Beach, the largest in the world, located in southern Rio Grande do Sul (240 km, Statista | Travel2next), and Forno Grande Beach in Búzios, Rio de Janeiro, notable for its unusual pink sand — likely the most remarkable of all Brazilian beaches (Viagem e Turismo | Turismo Buzios).

TIDAL ZONE

A recent global remote sensing analysis estimated that Brazil has 5,389 km² of tidal flats, ranking it as the 7th country with the largest tidal flat areas (Murray et al., Nature, 2018). Maranhão state includes the area with the highest tides in Brazil, up to 7m in São Marcos Bay near São Luís city (Baías do Brasil | Czizeweski, Dissertation, 2019).

BRAZILIAN MARINE ECOREGION

Brazil has 8 ecoregions in marine Atlantic in three blocks: North Brazil Shelf (Guianan, Amazonia), Tropical SW Atlantic (Sao Pedro and Sao Paulo Islands, Fernando de Naronha and Atol das Rocas, NE Brazil, E Brazil, Trindade and Martin Vaz Islands), and Warm Temperate SW Atlantic (SE Brazil and Rio Grande), being two tropical and one temperate (Takeshape | Bioscience, 2007).

DEEPEST POINT

The lowest point of the Brazilian EEZ and, therefore, of the entire national territory, can be found by accessing the Ocean Basemap (ArcGIS), activating 'layers', selecting ArcGIS Online mode, searching for 'Brasil ZEE', and activating the correct layer for a visual search. Then, the Bathymetric Data Viewer (NOAA) helps to obtain the exact point. The exact point is located at the approximate coordinates of 25°43'12" W 19°25'40.8" S, reaching a depth of -6182m, and does not have an official name, being 348 km from Martim Vaz island and 1,430 km from the mainland, at the latitude of Bahia.

DEEP OCEAN RESEARCH

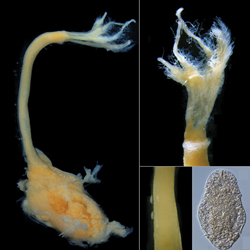

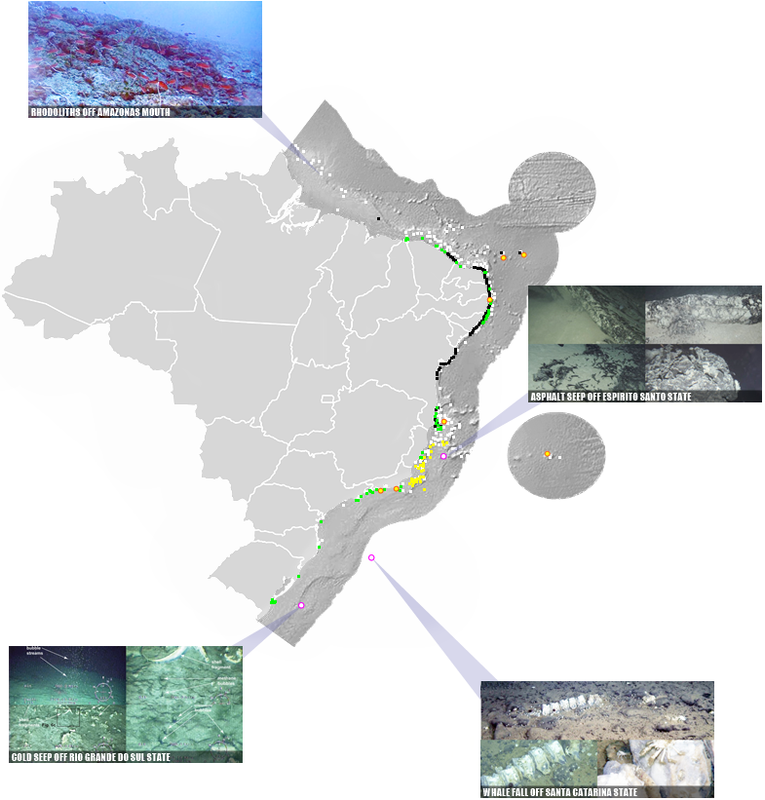

Knowledge of Brazil’s deep-ocean environments has expanded significantly in recent years, largely due to partnerships with niponic research institutions. For excellent prospecting work along the southeastern continental margin, see several studies published in 2017 (Editorial), and deep sea research in 21010-2020's, including investigations in the São Paulo Ridge (deep-sea ecosystems, Perez et al., Frontiers in Marine Science, 2020), the Rio Grande Rise (benthic megafauna: Ferraz Corrêa et al., Pre-print, 2022 | benthopelagic megafauna: Perez, Deep Sea Research, 2018), among others. Additional deep-sea research using submersible vehicles includes discoveries of new sponge species at the mouth of the Amazonas River (Moser et al., Zootaxa, 2022 | Zenodo). For the most comprehensive reference on Brazilian deep-sea biodiversity, consult the eponymous volume by Sumida et al. (Springer, 2020).

4 BORDERS

Brazil has 14,691 km of land borders, the 3rd longest in the world, and shares frontiers with 10 countries — ranking either 4th or 3rd globally depending on whether only Metropolitan France is considered. The country also has 10 single-line borders, placing it 11th worldwide and first in the New World (some European countries have numerous single-line borders, Wikipedia).

Administratively, Brazil’s border zone includes 121 municipalities across 11 states, covering roughly 1.4 M km² and inhabited by about 730K people. Brazil also has nine international tripoints: six located in rivers, one on a mountain summit, and the two in deep within the Amazon forest. Its border with Bolivia extends for 3,403 km, the 8th longest international border in the world (Statista). For details on specific tripoints, see BR/GU/VZ (GOV.BR), BR/VZ/CL (X), and BR/BL/PAR (Amboro Tours). A comprehensive list of public documents — treaties, reports, collections, maps, and related links — concerning Brazil’s borders is available at PCDL (MRE).

5 ANCIENT GEOLOGY

Present-day Brazil was part of the ancient continent Pangea, a term coined by Alfred Wegener in his 1920 book - including, most visible evidence of this split is in the similar shape of the coastlines of modern-day Brazil and West Africa. According to the probable distribution of the supercontinent, present-day Brazil had land connections with its present-day neighbors and with several West African countries, from Sierra Leone to Namibia. From 550 to 180 M years ago, Brazil was part of Gondwanaland, the southern continent, maintaining its same neighborhood in Pangaea. This continent follows a set of high-intensity events of the Neoproterozoic period, called the Brasiliano Orogeny Wikipedia). A high interest map for similar geology of northern South America and W Africa is available in Steel Club (SEE).

POSITION OF BRAZIL IN PANGAEA 220 M YEARS AGO, AND IN GONDWANA 150 M YEARS AGO (DINOSAUR PICTURES)

6 RELIEF

As a portion of Earth’s dynamic surface, Brazil features a complex geological basement, a dense network of rivers, multiple layers of vegetation, the climatic influence of the atmospheric gas layer, and a rugged surface that includes numerous elements such as mountains, valleys, plains, lagoons, canyons, sinkholes, caves, wetlands, waterfalls, and many others.

ALTUTUDES

Brazil has an average altitude of 325m above sea level. Among Brazilian states, the one with the highest average elevation is the Distrito Federal itself, at 1,035m, followed by Minas Gerais (734m) and Santa Catarina (677m). The state with the lowest average elevation is Amazonas, at just 102m — ironically, it is also home to Brazil’s highest point (Nexo Jornal).

Among Brazilian municipalities, 176 are located at elevations exceeding 1,000m, being the highest city Campos do Jordão (SP), at 1,587m, followed by at least nine cities in Minas Gerais, with Itamonte ranking second at 1,576m. Notably, 120 of these 176 high-altitude municipalities are located in Minas Gerais (Nexo Jornal).

Brazil no has surface below sea level.

MOUNTAINS

Contrasting to the Andes, which rose to elevations of nearly 7,000 m in a relatively recent epoch and inverted the Amazonia direction of flow from westward to eastward, Brazil's geological formation is very old. Precambrian crystalline shields cover approx 2/5 of the territory, especially its central area.

Eastern Brazil harbours the second most extensive South American network of mountain ranges, surpassed only by the Andes. The Serra da Mantiqueira Range and the Espinhaço Range (hereafter Mantiqueira and Espinhaço) are two nearly connected main orogenic belts of southeastern Brazil. Together, these highlands are distributed along a broad latitudinal range (10°S–24°S), extending approximately 1600 km from north to south, reaching up to 2890 m high. Mantiqueira Range is divided into two sections: southern Mantiqueira extends from E São Paulo state along the southern border of Minas Gerais state, whereas the northern section is on the border of the states of Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo. Espinhaço is also divided into two main sections: the Septentrional Espinhaço in Bahia State and the Meridional Espinhaço, mainly in Minas Gerais State, with the Quadrilátero Ferrífero (hereafter Quadrilátero) region representing its southernmost mountain formation. The Mantiqueira is fully embedded within the Atlantic Forest domain (AF), while the Meridional Espinhaço is in a transitional zone between the AF to the east and the Cerrado domain to the west, both global biodiversity hotspots. Septentrional Espinhaço, despite being influenced by the AF and Cerrado, lies within the Caatinga domain (Brunes, T.O. et al., Systematics and Biodiversity, 2023).

BRAZILIAN FIVE MAXIMAL POINTS AT RELIEF SHADED IN GREEN TO YELLOW LAYERS

Regarding the list of Brazil’s highest points, we follow the discussion proposed by Almanaque Z (SEE), which adopts the concept of maximal points and abandons the traditional terminology of 'culminating points', 'highest mountains', and similar labels. Under this criterion, Pico da Neblina and Pico 31 de Março are understood as parts of a single topographic unit, whose maximal relief is Pico da Neblina (a topic already well addressed in an excellent article published by Alta Montanha). Likewise, Pico do Calçado, Pico do Cristal, and Pico da Bandeira belong to a single unit, represented by its maximal relief: Pico da Bandeira. In this way, the five maxinal points in Brazil (all over 2,730m) are the ones that follow ahead. Brazilian maximal point (Pico da Neblina, 2,992m) is only the 71st highest in the world (Wikipedia), smaller than the respective for all neighbours except Guianas, Paraguay and Uruguay, evidencing the low altitude of the national territory - by the way, Brazil has only 320m of average altitude, being in position 118 in the ranking of highest countries (Wikipedia). Pico da Bandeira in Serra do Caparaó (2,892m), the second highest maximal points in country, is remarkable for being the Brazilian mountain with the greatest topographic isolation: 2,344 km (Wikipedia). In Americas, only Aconcagua, Mount McKinley, Pico de Orizaba and Mount Whitney are more topographically isolated than Mount Caparaó, and in the entire world, there are only 20 more isolated mountains.

On the upper slopes of Pico das Agulhas Negras, in the Itatiaia Massif, lies probably the highest spring in Brazil, at an altitude of 2,700m (Brazil in Line/Singularities).

A tepui is a dome-shaped, flat-topped mountain formation found in northern South America, especially in Venezuela, which hosts the most prominent examples of these features. Only two classic tepui formations occur in Brazil: Mount Roraima, of which Brazil contains only a tiny portion, and the Serra do Aracá, the southernmost true tepui of the Guiana Shield and the only tepui entirely within Brazilian territory (Wondermondo), with an average elevation between 1,000 and 1,200 m, reaching 1,750 meters at its summit.

The mentioned altitude of Mount Roraima Tepui below is not that of the top of the mountain, but that of the geodesic mark at the triple point of the borders of Brazil, Venezuela and Guyana — this landmark is the highest point of the mountain that is at least partially in Brazilian territory. The highest point of Mount Roraima as a whole is located in entirely Venezuela's side (Wikipedia), or, by recent works, in Guyana's side (Reddit/Mountainneering). To follow a beautiful expedition to the top of Serra do Imeri in Pico da Neblina, see SPOT Brasil (YT/2018).

GEOLOGICAL MONUMENTS

The Brazilian territory encompasses a wide variety of landforms associated with rocky outcrops, unevenly distributed across different regions of the country. Among the most prominent formations are the numerous inselbergs found in northern Ceará (as Pedra da Galinha Choca), eastern Minas Gerais, Espírito Santo, and northern Rio de Janeiro — isolated structures that rise abruptly from the surrounding landscape, being Pedra da Gávea is the largest coastal monolith in Brazil (Wikipedia), while Pedra Riscada is the largest monolith and tallest rocky wall in Brazil (CBG/2017). In Paraíba, Lajedo de Pai Mateus stands out as a notable example of residual relief, while the sandstone formations of Vila Velha, in Paraná, display shapes sculpted by intense weathering and erosion processes. In Goiás, the Pedra Azul State Park showcases large, rounded granite blocks, while the Chapada dos Veadeiros National Park contains deep canyons and towering quartzite cliffs. These geomorphological features highlight the geological complexity of Brazil and reflect the long-term influence of exogenous processes over geological time. In Campos Belos, in northeastern Goiás, the only — and truly spectacular — fairy chimney formations in the entire country can be found (G1 | Metropoles).

Among Brazil’s geological monuments, the country’s numerous canyons stand out. Notable examples include the Poty River Canyon in Piauí, the São Francisco Canyon between Bahia and Pernambuco, Talhado Canyon in N Minas Gerais, Guartelá Canyon in E Paraná — the longest in Brazil and the sixth longest in the world (30 km long, Wikipedia) — as well as the canyons of SE Santa Catarina and NE Rio Grande do Sul, including Itaimbezinho, the most emblematic canyon in the country (Brazil in Line/Singularities).

Araguainia dome a 40-km impact crater located on the border between the Brazilian states of Mato Grosso and Goiás, near the villages of Araguainha and Ponte Branca — it is the largest known impact crater in South America, the 15th largest in the world (Wikipedia), and the 5th largest in the Southern Hemisphere (Wikipedia).

Sandy formations are common in Brazil, with three standing out prominently: the Lençóis Maranhenses (he largest of all, in NE Maranhão, Revista Fapesp), the dune fields of Jalapão (E Tocantins, scenic, Guia Melhores Destinos), and the Xique-Xique Paleodunes (N Bahia, largest paleodunes in Brazil, SIGEPE/CPRM).

/s.glbimg.com/jo/g1/f/original/2011/12/26/lajedo1.jpg)

7 GEOMORPHOLOGY

Brazil exhibits a great diversity of soils, rocks, and minerals, reflecting its complex geological history and climatic variety. Most of the territory is dominated by Oxisols, Ultisols, and Entisols, while colder or more arid soil types, such as Chernozems and Andosols, occur only in residual areas. The country also hosts extensive rock formations, from ancient igneous and metamorphic rocks to recent sediments, as well as rich mineral deposits, including iron, bauxite, and manganese, which support important economic activities.

SOILS

The World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB) classifies 32 major soil groups worldwide (Wikipedia), whereas the Sistema Brasileiro de Classificação de Solos (SiBCS) recognizes only 13 main soil types within the country (Brazilian Soils). These two classification systems are conflicting. Despite the diversity of 25 different soil types in WBR critery, the vast majority — about 70% — consists of Oxisols, Ultisols, and Entisols, while Chernozem and Andosol soils occur in the country only in trace amounts.

24 soil type by WBR criteria are known in Brazil: Andosol (AN, SEE, with a single manch in South America outiside Andes in Rio Grande do Sul state/SEE), Umbrisol (UM, virtually unknown in Brazil/SEE, however present in some areas, SEE), Histosol (HS, SEE), Anthrosol (AT, man made soil, not recognised at a high classification level in Brazil, SEE; include black-soil from Amazon), Technosol (TC, man made soil, not recognised at a high classification level in Brazil, The Soils of Brazil), Leptosol (LP, SEE), Solonetz (SN, SEE), Vertisol (VR, SEE), Gleysol (GL, SEE), Podzol (PZ, SEE), Plinthosol (PT, SEE), Planosol (PL, SEE), Nitisol (NT, SEE), Ferralsol (FR, SEE), Chernosol (CH, very dark and well-structured topsoil, secondary carbonates, SEE, known in Brazil in southern Rio Grande do Sul state, SEE), Kastanozem (KS, SEE, known in some regions of northeastern Brazil, SEE), Phaeozem (PH, SEE), Acrisol (AC, SEE), Lixisol (LX, SEE), Alisol (AL, SEE), Luvisol (LV, SEE), Cambisol (CM, SEE), Fluvisol (FL, SEE), Solonchak (SC, SEE, rare in Brazil/SEE), and Arenosol (AR, SEE) and six are unknown or almost unknown in Brazil: Cryosol (CR, permafrost-affected, SEE), Gypsisol (GY, SEE), Calcisol (CL, SEE), Stagnosol (ST, SEE), Retisols (RT, former Albiluvisol, SEE), and Regosol (RG, SEE). Unfortunately, there is no consistent information available on one soil type: Durisols (DU).

Loess is not exactly a soil type but rather a parent material — a fine-grained, wind-deposited dust rich in silt and calcium carbonate, laid down during glacial periods. It has a predominantly silty texture (up to 70–80% silt), high porosity, good drainage, and great natural fertility when it evolves into Chernozems or Phaeozems. However, it is highly erosion-prone. Loess typically has a yellowish to gray color and a granular, stable structure with strong natural aggregation. It originates from glacial dust transported by wind during cold, dry periods (mainly the Pleistocene). Major loess deposits occur in northern China (the Loess Plateau, the world’s largest), Central and Eastern Europe (Germany, Ukraine, Poland, Hungary), the central USA (Missouri, Iowa, Illinois), and Argentina (Pampas and Andean forelands).

Brazil lacks significant loess deposits, precisely because it was never covered by continental ice sheets and has no large cold-dust plains. Some fine-textured soils in southern Brazil may resemble loess in particle size, but they are of volcanic or sedimentary — not glacial eolian — origin.

MOSAIC OF BRAZILIAN SOILS (BRAZILIAN SOIL CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM | MAP | SYNGENTA DIGITAL) AND SOME EXAMPLES

MINERALS

Brazil is extremely rich in gemstones and minerals, displaying a diversity found in few other countries. It is home to a wide range of colored quartzes (amethyst, citrine, rose quartz), tourmalines — including the famous Paraíba tourmaline, imperial topaz (from Ouro Preto, the world’s only major deposit), and various beryls (aquamarine, emerald, morganite, heliodor), as well as diamonds and strategic elements such as niobium, tantalum, beryllium, and lithium, all essential to modern technologies. The country also contains rare gem-bearing pegmatites in states such as Minas Gerais, Paraíba, and Rio Grande do Norte.

In Brazil, rubies are found in Bahia and Santa Catarina, but they do not reach the quality or grandeur of those from the great Asian producers such as Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar, India, and Sri Lanka (Thesis | Monograph). Some minerals mentioned as rare or unknown in the country have, in fact, been confirmed through verified findings — such as glaucophane (IG/USP), realgar (Water), and coesita (Revista Fapesp). In total, Brazil is the type locality for 65 minerals — a relatively small number compared to major global players such as the USA and Russia (Revista Fapesp).

Nevertheless, there are notable gaps directly related to the absence of specific geological environments, such as recent volcanism, active subduction zones, ultra-high-pressure metamorphism, and extremely arid climates.

When it comes to valuable gemstones, it is quite common for many of them — including some of the rarest and most prized — to occur in several regions around the world. At the same time, certain species and varieties are extremely restricted, sometimes found in only a few localities or even a single country, such as lapis-lazuli (deep blue, typical of the Andes in Afghanistan, Chile, and smaller amounts in Russia, Angola, Argentina, Burma, Ethiopia, Pakistan, Canada, Italy, India, and in the USA in California and Colorado - Wikipedia), jadeite (a translucent green jade found in Myanmar, Guatemala, and Japan), nephrite (another jade variety, gray-green, common in China, New Zealand, Russia, and Canada), benitoite (glassy blue, a rare mineral from California and Australia), tanzanite (violet-blue, from Tanzania), larimar (light-blue pectolite, from the Dominican Republic, associated with recent andesitic volcanism), painite (reddish-brown, from Myanmar, one of the rarest minerals in the world, found in boron – aluminum metamorphic pegmatites unknown in Brazil), and poudretteite (light pink, from Canada and Myanmar, associated with rare alkaline pegmatites, also absent in the country). Brazil hosts an immense diversity of gemstones, including diamonds, rubies, sapphires, topaz, and many others. Among the most notable are the near-exclusive Paraíba tourmaline (an elbaite that occurs primarily in the Borborema Pegmatite Province in the states of Paraíba and Rio Grande do Norte — with smaller deposits in Nigeria and Mozambique, and which is the rarest and most valuable of all tourmaline varieties, Desgeoeduorg | Brazil Paraiba Mine) and amethyst (for which Brazil holds the world’s largest known mine, located in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Top Trip Adventura).

Among metallic minerals, those absent or extremely rare in Brazil include nickel from young ultramafic laterites (common in Indonesia and the Philippines), molybdenum (MoS₂, typical of Andean porphyry copper deposits in Chile and the USA, which are absent in Brazil), rhenium (associated with recent volcanic systems in the Chilean Andes), tungsten (scheelite and wolframite, abundant in China, Portugal, and Bolivia, but found in Brazil only in small occurrences), palladium and platinum (which occur in large quantities in Russia and South Africa, while Brazil contains only minor traces in Carajás and Goiás, lacking large layered complexes such as the Bushveld), and mercury (cinnabar, common in Spain, the USA, and Mexico, formed in hydrothermal volcanic settings, which are not present in Brazil).

Minerals formed under glacial, arid, or volcanic conditions are also absent, such as natron (Na₂CO₃·10H₂O, typical of alkaline desert lakes in Africa), trona and massive halite (evaporites from desert basins that occur in Brazil only as thin layers), and native sulfur and orpiment (As₂S₃, AsS, produced in fumaroles and young hydrothermal environments — nonexistent in Brazil due to the lack of recent volcanism). Finally, metamorphic and exotic minerals absent from Brazil include microcrystalline impact diamond (formed in young impact craters such as those in Siberia and Canada — whereas Brazilian craters are ancient). Likewise, lawsonite form under high-pressure, low-temperature conditions, typical of subduction zones — a geological feature not found in Brazil.

ROCKS

VOLCANIC ROCKS ABSENT IN BRAZIL

Brazil hosts extensive ancient basaltic flows, such as those of the Serra Geral Formation (Cretaceous), but has had no active volcanism for tens of millions of years. Consequently, volcanic types typical of active magmatic arcs are absent, including andesites (common in the Andes, Mexico, Japan, Indonesia, and the Mediterranean), dacites (more silica-rich varieties found in the Andes and the Philippines), and young rhyolites (felsic rocks from recent explosive eruptions, e.g., Yellowstone, New Zealand, and the Andes). In Brazil, only ancient rhyolites occur, associated with Proterozoic magmatic provinces such as Paraná–Etendeka.

Also absent are recent tholeiitic basalts (typical of oceanic ridges and oceanic islands such as Hawaii, Iceland, and the Galápagos) and pumice, obsidian, and fresh volcanic ash, products of explosive volcanism that no longer exists in Brazil.

HIGH-PRESSURE METAMORPHIC ROCKS: RARE OR ABSENT

Despite its long and complex geological history, Brazil has almost no record of rocks formed in deep, recent subduction zones. Eclogites, formed under high pressure and typical of Norway, the Alps, Japan, and Chile, occur only rarely and are ancient. Similarly, blueschists, formed under high-pressure and low-temperature conditions (as in the Andes, California, and Japan), are practically absent.

SEDIMENTARY ROCKS OF GLACIAL OR EXTREMELY ARID ENVIRONMENTS

Because Brazil has tropical climates and has not undergone recent continental glaciations, modern glacial sediments such as tillites (glacial diamictites) — common in Antarctica, Canada, and Scandinavia — are missing. Only very old tillites from the Paleoproterozoic (e.g., Jequitinhonha Formation) are found.

Thick evaporite sequences (halite and massive gypsum), typical of closed arid basins such as the Dead Sea, the Sahara, and large Texas basins, are also absent, occurring only as thin and ancient layers (Araripe and Sergipe basins). Likewise, young tuffs and ignimbrites, products of recent explosive volcanism, are not found in Brazil.

ULTRAMAFIC ROCKS

Brazil contains some ancient ultramafic rocks, such as komatiites and peridotites, but lacks young, active kimberlites, typical of South Africa and Siberia. Ancient and inactive kimberlites are found in Minas Gerais and Goiás, and lamproites and carbonatites occur in places such as Araxá and Catalão, though all are remnants of ancient activity. Similarly, young komatiites are absent — only very old examples are preserved.

8 LAND CAVES

Caves are a striking element of the planet's landscapes, and they are as diverse as they are fascinating, occurring both on land and underwater, in various latitudes and lithologies, and varing in size, inclinations and many other elements. An excellent overview of caves in Brazil — including their main systems and lithologies — can be found in Auler & Farrant (University of Bristol Spelaeological Society, 2006), despite the age of the text.

NUMBERS

Data from 2023/2024 indicate that Brazil has 26,046 documented caves. Minas Gerais is the state with the largest number of known caves, totaling 12,911 entries (49.57%), followed by Pará (3,224), Bahia (2,017), Rio Grande do Norte (1,373), and Goiás (1,136). Among the Brazilian biomes, the Cerrado contains 12,008 caves, while the Pampa and Pantanal have the fewest records, with only 38 and 12 respectively (ICMBIO).

LITHOLOGY

Brazil exhibits high lithological diversity in its cave systems: although most caves are formed in limestone, several other lithologies are also represented. In marble [1], the Casa de Pedra Cave in Rio Grande do Norte state (Martins municipality) is highlighted, cited in various references as the largest of its type in Brazil (110m, Sertão Dourado). In granite [2], the Riacho Subterrâneo Cave, in Itu municipality (SP, 1,415m, Bichuette et al, Neotropical Biology and Conservation, 2017), is recognized as the largest granite cave in Brazil, in the Southern Hemisphere, and the sixth largest in the world. Volcanic caves [3] — or lava tubes — are common in Hawaii, the Galápagos, and the Canary Islands, but are rare in Brazil, known in the country only from four caves documented in SW Paraná state (Casa de Pedra and Perau Branco in Palmital municipality, Dal Pae in Marquinho municipality, and Pinhão in Pinhão municipality, SINAGEO/2016 | G1). In quartzite [4], the largest is the Martiniano II Cave, in Ibitipoca municipality (MG, 4770m, CBE/2021). In gneiss [5], the Chacina Cave in São José do Barreiro municipality (SP, 406m, CBE/2019) stands out as the largest of this lithology in Brazil. In sandstone [6], the largest national cave is Aroe Jari, in Chapada dos Guiamarães municipality (MT, 1,550m, Interativa Pantanal). In iron ore [7], being spatial units predominantly composed of ferruginous lithotypes that, in Brazil, are restricted to few regions outside the state of Minas Gerais (Iron Quadrangle, West border of Serra do Espinhaço and Rio Peixe Bravo Valley), Pará (Serra de Carajás, the large cluster of ferrugineous cave systems in Brazil, Ruchkys, UA et al, Mercator, 2024), Bahia (Rio São Francisco Valley) and Mato Grosso do Sul (Urucum plateuau) states, based on Gomes, M. et al. (Revista Colombiana de Geografía, 2019).

There is no updated data on the distribution of caves by lithology in Brazil. Data from 2011/2012 estimate around, when there were only 10,220 known caves in Brazil, that they were distributed by lithology as follows: 7,000 karst caves, 2,000 iron ore caves, 510 quartzite caves, 510 sandstone caves, and 200 caves in other rocks (Rocha, MC et al., Brazilian Geographical Journal, 2018).

Caves formed by the growth of tufa are relatively uncommon. Only two are registered in the Cadastro Nacional de Cavernas of the Brazilian Speleological Society (consulted on 28 January 2011, although cavities formed by tufa growth do occur in the Serra da Bodoquena, along the Mimoso River, but remain unregistered): Abrigo-sob-rocha do Caxangá (Rio de Janeiro state) and Rio Fria Cave, Barra do Turvo municipality, the largest and most emblematic example of this highly singular type of cave in Brazil, with only 80 m of mapped length and an elevation difference of 11 m (Sallun Filho et al, Espeleo-Tema, 2011).

Within a broad concept of chemosynthetic caves, the Monte Cristo Cave can be considered a potential candidate for being the first — or possibly the only — chemosynthetic cave in Brazil. This quartzite cave, located in Diamantina, Minas Gerais state, is distinguished by its peculiar characteristics, including strong nutrient limitation, elevated CO₂ concentrations, and a unique microbial community (especially members of the class Ktedonobacteria, also possess a high diversity of genes involved with different biogeochemical cycles, including reductive and oxidative pathways related to carbon, sulfur, nitrogen, and iron). The cave has been studied as an analog model for life on Mars and exhibits a high diversity of genes involved in iron and manganese cycling, with significant implications for astrobiology and biotechnology (Bendia, A. et al, Astrobiology, 2021 | Firrincieli, A. et al., BiorXiv, 2025).

RECORDS

The two largest Brazilian caves in horizontal projection are Toca da Boa Vista (114 km, 24th largest cave worldwide and the third in southern Hemisphere after Marosakabe Cave in Madagascar and Builita Cave in Australia, Wikipedia) and Toca da Barriguda (35 km), both in Campo Formoso, Bahia. The deepest caves in Brazil are Caverna do Centenário cave (484 m) and the Bocaina Cave (404 m), both in Mariana, Minas Gerais state (Grupo Bambuí). Only five caves in Brazil have entrance portals measuring 70 m or more, the largest of which is the entrance of the Casa da Pedra cave, being the largest cave entrance in the world (215 m high, Iporanga, São Paulo state, Bambuí Speleo).

Perna de Bailarina stalactite is the world’s largest stalactite, located in the Peruaçu Caves National Park, at the entrance of the Janelão Cave. It measures 28m in length, the result of a slow and continuous geological process that began around 140,000 years ago, with a growth rate extremely slow — about 1cm/100y (Revista Oeste | G1).

SINKHOLES AND CENOTES

A cenote is a natural pit, or sinkhole, resulting when a collapse of limestone bedrock exposes groundwater. The term originated on the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico, where the ancient Maya commonly used cenotes for water supplies, and occasionally for sacrificial offerings. The term cenote, originally applying only to the features in Yucatán, has since been applied by researchers to similar karst features in other places such as in Cuba, Australia, Europe, Brazil (National Geographic Brazil) and USA. (Wikipedia).

The largest dry sinkhole in Brazil is Araras Sinkhole, located in NE Goiás state, with about 105m deep and 295m wide, sheltering in its interior a small forest environment in contrast to the low vegetation of its surroundings (Notas Geo | Almanaque Z/2022). Lagoa Azul, a flooded doline located in the municipality of Niquelândia, Goiás state, is identified by the Bambuí Group as the deepest dive cave in Brazil with 274m deep (Bambuí Speleo) and is widely cited in popular media as the country’s deepest dive cave in Brazil with 274m deep (Bambuí Speleo) - some references suggest depths of up to 320 m (Brasil Mergulho). However, unfortunately, there is no scientific literature confirming the doline’s depth, volume, funnel morphology, or possible connections with other cavities.

BIOLOGICAL RICHNESS

Águas Claras cave system is a cave system located in the municipality of Carinhanha (BA), approximately 24 km in length and composed of four limestone caves (Marconi Souza-Silva et al., Biodiversity and Conservation, 2021), recognized as the richest hotspot of subterranean biodiversity in the Neotropical region — 41 identified troglobic species across the following groups: Hexapoda (14), Arachnida (10), Isopoda (6), Diplopoda (7), Gastropoda (2), Turbellaria (1), and Actinopterygii (1). This system surpasses Toca do Gonçalo (also in Bahia) and the Areias cave system (southern São Paulo state), the only other two subterranean biodiversity hotspots known in South America (R. L. Ferreira & Marconi Souza-Silva, Diversity, 2023).

Mouras cave, located in SE Tocantins state, possibly has the largest diversity of species of bats worldwide, with 26 spp. collected, 3 ahead Tziranda Cave in Michoacán, Mexico (Barros, JS et al, Acta Chiropterologica, 2021).

UNBRAZILIAN TYPE OF CAVES

Brazil does not includes gypsum caves (Gypsum karst of the world: a brief overview) nor chemoautophoric caves (Movile Cave). In world has 80 caves with more than 1km of depth, none in Brazil (Profundezas).

KARST AREAS (▇) AND LAND CAVES (❍) IN BRAZIL (KA | MDPI), AND SOME RELEVANT CAVES IN IMAGES

9 BRAZILIAN SISMIC and VULCANISM ISSUES

The geological stability of Brazil is a result of its location within the South American Plate, far from active tectonic zones. This ensures the absence of active volcanism and violent earthquakes, creating a relatively safe environment in terms of natural disasters related to plate tectonics.

ACTIVE VOLCANISM

Although Brazil has some areas of extinct volcanic activity, such as in the south and southeast regions (where the Paraná Traps and some volcanic structures in the state of São Paulo are located), there are no recent manifestations, such as volcanoes, lava fields, geysers, or deep marine hydrothermal vents. The youngest continental magmatism in Brazil (19.7 Ma) is represented by Pico do Cabugi, the only extinct volcano in the country that still preserves its original shape, and one of several volcanic necks of the Tertiary alkaline basaltic province of Rio Grande do Norte (SIGEP). It is located in the municipality of Angicos, in Rio Grande do Norte state (Clube Candeias), NE Brazil.

Central Brazil is home to the world's largest geothermal water complex unrelated to magmatism — hot springs emerge along a metamorphic terrain in two main locations in SE Goiás state, 35 km apart: Rio Quente, west of the Caldas dome (12 km lenght, Globo Reporter), featuring moderate temperatures (mean 37.5 °C), and Caldas Novas, east of the Caldas dome, exhibiting relatively higher temperatures, mean 41.9 °C (Lunardi & Bonotto, Geoenergy Science and Engineering, 2025 | Rosa, JWC et al, Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 2021) in 18 springs (Globo Reporter). Many sources highlight the Poço do Ovo, in NE side od Caldas Novas town, whose waters reach up to 57°C, as the hottest natural spring in Brazil (Globo Play | Caldas Novas | IMAGE).

EARTHQUAKES

Earthquakes in South America are typically shallower than 300 km or deeper than 500 km — the deep earthquakes concentrate in two zones: one that runs beneath the Peru-Brazil border (many details in Earth Jay Maps and Graphics) and another that extends from central Bolivia to central Argentina (Ciardelli et al., Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 2022). Preve, D’Espindula e Valdati (Geografia Física e Desastres Naturais, 2017) list all earthquakes in Brazil with magnitudes above 5 Mb recorded between 1900 and 2017. During this period, 40 events were identified, 27 of which are concentrated in SE Amazonas and in Acre, with the remaining ones are distributed across other parts of Amazonas (2), as well as Amapá (2), N Mato Grosso (3), NW Goiás (1), SE Santa Catarina (1), S Minas Gerais (1), Espírito Santo (1), E Pernambuco (1), and N Rio Grande do Norte (1). Among the earthquakes from this southeastern sector of Amazonas and Acre are the 4 largest events in the survey, as well as 5 of the 7 largest ever documented in the country, making this area the most prone to earthquakes in the entire country. The largest of all was the earthquake with its epicenter in Ipixuna (AM), which occurred on June 20, 2003, and reached a magnitude of 7.1 Mb.

WORLD EARTHQUAKES SINCE 1898 (SYFY) AND A FOCUS IN BRAZIL

It is important to note that this survey does not include data after 2017. More recent years contain well-documented seismic events, including potential earthquakes stronger than those listed here.

SOUTH AMERICAN PLATE (AND THEIR 8 NEIGHBORING) AND LARGEST EARTHQUAKES IN BRAZIL BETWEEN 1900-2027 | SEE

10 CONTINENTAL WATERS

Out of all the water on Earth, saline water in oceans, seas and saline groundwater make up about 97% of it. Only 2.5-2.75% is fresh water, including 1.75-2% frozen in glaciers, ice and snow, 0.5–0.75% as fresh groundwater and soil moisture, and less than 0.01% of it as surface water in lakes, swamps and rivers. Freshwater lakes contain about 87% of this fresh surface water, including 29% in the African Great Lakes, 22% in Lake Baikal in Russia, 21% in the North American Great Lakes, and 14% in other lakes worldwide (Wikipedia).

RIVERS

Brazil has the largest net of rivers worldwide, and the largest renowable water resources, with 8,233 km³, followeb by Russia with 4,508 km³ (Wikipedia). Brazilian waters cover about 55,325 km² of the country (Wikipedia), the 14th largest water area in World.

There are 193 rivers over 1,000 km worldwide, mainly in Russia (39), USA (28), China (24), Brazil (22), Canada (14) and Australia (7). The largest rivers that belong to a single country are Yangtze (China), Yellow (China), Lena (Russia), Mackenzie (Canada), Murray (Australia), Volga (Russia), San Francisco (Brazil) and Lower Tunguska (Russia). The three largest rivers in the world that flow into another river are Brahmaputra (India, China, Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan), Madeira (Brazil, Bolivia, Peru) and Purus (Brazil, Peru) — for details, see Wikipedia.

All river flows from Brazil run into the Atlantic Ocean — that is, Brazil no has endorheic basins.

The Amazonas River (Amazon–Ucayali–Tambo–Ene–Mantaro), at 6575 km in length, is the second-longest river in the world after the Nile (Nile–White Nile–Kagera–Nyabarongo–Mwogo–Rukarara) at 7,078 km (S. Liu et al, International Journal of Digital Earth, 2000). It is, however, the largest river by discharge, accounting for roughly 1/5 of all freshwater entering the global ocean—greater than the combined discharge of the next seven largest independent rivers. The Amazon enters Brazil carrying only about one-fifth of the volume it ultimately releases into the Atlantic Ocean, yet even at this point its flow already surpasses that of any other river in the world (Wikipedia). The São Francisco River has a length of 2,914 km, it is the longest river running exclusively within Brazil and the fourth-longest in South America (Wikipedia). Among the six largest rivers in the world by discharge (baed on Wikipedia), three belong to the Amazonas system: Amazonas Rier (209,000 m³/s), Negro River (35,943 m³/s), and Madeira River (31,200 m³/s) (Wikipedia; SEE). Of the top eleven rivers globally in terms of discharge, seven are located in South America.

For material on the sources of the Amazonas river, see Hema Pelo Mundo (YT/2022) and Espírito Livre Expedições (YT/2021). For aerial footage of the Amazonas mouth, including segments of a flight from Belém to Macapá, see the video by Bruno Augusto (YT/2021).

As for river mouths in Brazil, the two most notable are the colossal mouth of the Amazon River — mentioned above — and that of the Parnaíba River, which splits into several branches and forms the most characteristic delta in the country (Feldens et al., Geo-Marine Letters, 2014).

Brazil’s rugged relief and extensive river network give rise to tens of thousands of waterfalls: the most voluminous is the Iguaçu Falls (Iguaçu River, SW Paraná, average rate of 1,746 m³/s, maximum recorded flow was 45,700 m³/s on 9 June 2014, Wikipedia), the longest — indeed, the longest in the world — are the rapids of the Yacuman River on the Uruguay River, along the border with Argentina (1,800m long, NW Rio Grande do Sul, Wikipedia), and the tallest in the country — 28 waterfalls exceed 200 meters in height — with the tallest being the Neblina Falls, in Rio de Janeiro state (450m high, Cachoeiras Gigantes).

Among fluvial islands, Brazil is a hotspot. The river systems in the north of the country create Anavilhanas, the largest flooded forest systems in the world (E.M. Latrubesse and J.C. Stevaux, World Geomorphological Landscapes, 2015), located on the Negro River in N Amazonas state; Marajó Island, the largest fluvio-marine island in the world (40.100 km², Wikipedia), vast and encompassing rivers, channels, and other island systems; and Bananal Island, the largest entirely riverine island on the planet (Wikipedia), located on the Araguaia River in SW Tocantins.

Tidal bores occur in various places around the world where specific geographical conditions exist, especially in areas with significant tidal ranges (Wikipedia | MAP). However, there is no official ranking or comprehensive study that determines the largest and most voluminous tidal bores globally — although the tidal bore in China is often referred to as the most voluminous on the planet (Wikipedia). In Brazil, tidal bores occur from Amapá to Maranhão, in several rivers, particularly near the mouth of the Amazon River, and are collectively known as pororocas. In the Amazon region, these bores can influence river levels over 800 km inland from the sea, making them the most inland-reaching bores known and unquestionably the largest in America Latina (Aguas Amazônicas | Surfer Today | Image/Mongabay), mainly observed on biannual equinoxes in September and March during a spring tide (Wikipedia). Unfortunately, the bore of the Araguari River, another notable one, ceased to exist in 2014 (Mar Sem Fim).

Finally, beyond the scenic beauty of Brazilian rivers connected to beaches, waterfalls, deltas, and more, several curious features are worth mentioning. These include the confluence of the Negro and Amazon Rivers in Manaus, Amazonas, where the contrasting colors of the waters create a striking visual effect (Wikipedia); the Azuis River in SE Tocantins, considered by some sources to be the 3rd shortest river in the world, measuring only 147 m in length (Wikipedia); and the Sucuri River, an extremely clear, crystalline river located in SW Mato Grosso do Sul (Correio do Estado).

LAKES

To discuss lakes in Brazil while maintaining fidelity to Portuguese nomenclature, we will use lagoa as the term for Brazilian lakes, if that is how they are known nationally.

Brazil has a very limited number of lakes, most of them small and lacking significant representation. In general, the most prominent types are coastal lagoons. Here we highlight six of the country’s most notable lakes. [1] Lagoa Araruama, in Rio de Janeiro state, is the second-largest saltwater lake in Brazil, the largest located entirely within the country, and largest permanent hypersaline lake in the world, covering 220 km². It surpasses other well-known hypersaline lakes such as the Great Salt Lake in USA, Lake Coorong in Australia, Lake Enriquillo in Dominican Republic, and Ojo de Liebre Lagoon in Mexico (Wikipedia). [2] Lagoa Juparanã, in Espírito Santo state, is the largest in area (62.58 km², Amorim Gonçalves, Dissertation, 2015) and in volume (0.5281 km³, Almanaque Z) freshwater lake entirely within Brazil, ranking second in both area and volume nationally, after Lagoa Mirim. [3] Lagoa das Palmas, also in Espírito Santo state, reaches a maximum depth of 50.7 m, a mean depth of 21.4 m, and a total volume of 0.22 km³, making it the deepest natural lake in Brazil (Barroso, GF et al, Plos One, 2014). [4] Lagoa Mirim is a freshwater lake and the largest lake within Brazilian territory, with an average area of approximately 3,749 km² (ranging from 3,381 to 3,863 km²), 2/3 of which lie in Brazil and 1/3 in Uruguay (Wikipedia). Its average depth is 4.5 m (maximum 16 m, Munar et al., SBRH, 2017), resulting in an estimated volume of 16.87 km³ (IPH, 1998). [5] Lagoa Mangueira, a saltwater lake in southeastern Rio Grande do Sul, covers 820 km² with a volume of 0.7 km³, making it the largest saltwater lake in Brazil (Artioli et al., Iheringia, 2009). [6] Lagoa Salgada, in northern Rio de Janeiro state, is notable for containing the only known occurrence in Brazil — and possibly South America — of recent columnar carbonate stromatolites (SIGEP).

Nhecolandia alkalyne lakes is a uncommon system of lakes (the unique system of alkaline lakes in Brazil) in the Pantanal subregion of Nhecolândia, comprising approximately 10,000 lakes along 24,000 km², predominantly shallow, with sizes ranging from 0.025 to 0.15 km², and primarily characterized by freshwater lakes, known locally as baías, with around 7% being saline-alkaline lakes or salinas (pHs above 9 or 10, high alkalinity and a high density of phytoplankton), surrounded by alkaline soils (Costa Silva, AR et al., Geoderma Regional, 2024).

SUBTERRANEAN WATERS

The Sistema Nacional de Informações sobre Recursos Hídricos (SNIRH) of Brazil identifies 151 porous aquifer systems (large amounts of water are stored in pores, which are voids inherent to the rock or soil matrix; in shades of blue on the map below), 26 karst aquifer systems (water flows through conduits that result from the enlargement of joints or fractures by dissolution in carbonate rocks; in shades of brown), and 4 major fractured systems (water circulates through fractures or small cracks, which are structures formed by processes that occurred after the rock’s formation; in green), totaling 181 systems across the national territory (Metadados/SNIRH).

MAP OF THE 181 AQUIFER SYSTEMS OF BRAZIL, COLOR-CODED INTO THE THREE MAIN GROUPS (SNIRH), AND DETAILS OF GUARANY AQUIFER

Guarani Aquifer System (GAS) represents the second largest aquifer in the world (after Great Artesian Basin, in Australia, Wikipedia) and the largest in Brazil, occupying 950,000 km² within the Paraná sedimentary basin at 8 states, reaching also in other three countries: Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay; 90 M people are directly or indirectly benefitting from the GAS exploitation (Teramoto, Gonçalves & Chang, Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, 2022).

There is an extreme lack of information about the artesian wells in Brazil. As artificial structures with a natural flow, they represent a unique category in hydrogeology. It is known that between 264, 300 (Geociências e Meio Ambiente), 350 (Brasil Escola) or 500 such wells are scattered along a strip about 30 km wide on each side of the Gurguéia River in southern Piauí state (Conejo, ANA, 2005), within the Cabeças Aquifer area, whose spontaneous water discharge is due to the confinement of the Cabeças and Serra Grande aquifers by the Longá and Pimenteiras formations, respectively, throughout the entire valley (about 400 km), ensuring shallow static levels and, occasionally, flowing artesian conditions, which reduce the cost of water extraction (Feitosa, CPRM, 2010). Considerable controversy surrounds these wells, especially regarding the high level of water waste they represent (Folha de S Paulo, 2000). The largest artesian well of Brazil, Violeto I, located in Alvorada do Gurguéia, currently reaches about 25 m in height, though older reports describe jets as high as 70 m. Some sources even describe it as the second largest in the world of its kind — without specifying which one would be the first (Click Petroleo e Gás, 2025).

FRESHWATER ECOREGIONS

426 freshwater ecoregions cover virtually the entire non-marine surface of the earth (Feow), 24 in Brazil, the smallest in Brazil is the Chaco, with a small portion in Mato Grosso do Sul state.

11 CLIMATE

Despite the wide latitude and the relative variety of temperatures and rainfall rates throughout the national territory, Brazil is not a country of climatic extremes. In few words, the south of the country has higher records of cold temperatures, while the northeast has a history of low rainfall.

TEMPERATURES AND RAINFALL

The driest place in Brazil is possibly the municipality of Cabaceiras, in the state of Paraíba, with an average annual precipitation of 336.6 mm based on 86 years of observations. The record high occurred in 1964, with 775.5 mm, and the record low in 1952, with only 23.8 mm (Carmem TB et al., Revista Educação Agrícola Superior, 2013). The wettest location in Brazil is the municipality of Calçoene, in the state of Amapá, with reported annual rainfall ranging from 4,165 mm (EMBRAPA) to 4,238.3 mm (station 825002, 1975–2006; Oliveira, LL et al., IEPA/AP, 2007).

However, the Koppen Brazil Github data, which highlights at the municipal level the variables temperature, altitude, and rainfall, and whose source could not be determined, identifies the cities of São Gabriel da Cachoeira (3619.6 mm) and Japurá (3527.8 mm) — both in Amazonas — as the wettest in Brazil, with Calçoene only in 3rd place (3344.3 mm). The list continues alternating between Amazonas and Amapá for several consecutive positions. Among the driest, the same reference cites São Domingos do Cariri (409.6 mm), Barra de São Miguel (421.3 mm), and Caraúbas (429.3 mm) as the driest, all in Paraíba, with Cabaceiras (429.3 mm) in only 5th place. Paraíba, Pernambuco, and Bahia alternate positions among the driest municipalities in the country.

Brazil ranks as the 43rd wettest country worldwide, with an average annual precipitation of 1,761 mm (Global Economy).

The highest temperature officially registered in Brazil was 44.8 °C (112.6 °F) in Araçuaí, Minas Gerais state, on 19 November 2023 (G1). The lowest temperature officially recorded in Brazil was −14 °C (7 °F) in Caçador, Santa Catarina state, on 11 June 1952 (CIRAN/EPAGRI).

ANNUAL CLIMATOLOGICAL NORMALS OF TEMPERATURE AND PRECIPITATION FROM 1991 TO 2020 IN BRAZIL (INMET)

Brazil's cold record is less extreme than that of mostly tropical countries like Botswana, Mexico, Peru and Australia; in turn, the heat record is less extreme than that of essentially temperate non-desert countries such as Azerbaijan, Myanmar, Nepal, Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, North Macedonia, Portugal, Russia, Serbia, Spain, Canada, as well as the records of Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay and Guatemala (Wikipedia).

As an essentially tropical country, temperatures in Brazil are almost always above freezing, reaching their lowest levels in late autumn, winter, and early spring, sometimes with snow in elevated areas. Due to its geographic position, the southern region is the coldest, particularly in highland areas — an aspect deeply rooted in popular culture, public policies, and several other domains. Various metrics can be applied to scientifically determine which specific part of the country can be considered the coldest. Herter, FG & Wrege, MS (Documentos/Embrapa, 2004 | MAP) calculated and mapped the number of hours with temperatures equal to or below 7.2°C in southern Brazil, producing a detailed map. This map highlights some zones in Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul that record 500h or more under this temperature threshold. The largest of these areas covers SE Santa Catarina (10 municipalities) and NE Rio Grande do Sul (12 municipalities), which includes the only portions in the country exceeding 600h. Therefore, this is the region identified in this article as the coldest in Brazil

ARID DESERTS

It is widely recognized in Brazilian geographic culture that the northeastern semi-arid region is the driest part of the country. In addition, there is broad agreement in identifying a vast area in northern Bahia and southern Pernambuco as the most arid portion of Brazil (MAP | MAP | MAP) — a region we refer to here as the Canudos Arid Complex, which may, in the future, come to be known as the Canudos Desert. This area includes, within its diffuse perimeter, the first technically arid region identified in Brazil, a area of 5,763 km² located in the NC Bahia and covering the entire area of the municipalities of Abaré, Chorrochó and Macururé, in addition of area of Curaçá, Juazeiro and Rodelas, municipalities in Bahia that border the Pernambuco hinterland, revealed in a 2025 study (CEMADEN | MAP) and widely reported in the media (G1), with an aridity index of less than 0.2. It also comprises all sites classified as BSh — hot arid climate — in the Köppen system (Wikipedia), as well as the Raso da Catarina, a striking landscape often portrayed in the media as the 'Brazilian Atacama' (Fundaj | The Summer Hunter), with physiognomic similarities to the desert chaparrals of northern Mexico, the margins of the Kalahari, or the Australian scrublands. The Canudos Arid Complex does not, however, include geographic forms typical of true deserts, such as extensive dune fields, sandstorms, or salt flats

DISTRIBUTION OF SEMI-ARID AREAS AROUND THE WORLD AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE BRAZILIAN SEMI-ARID REGION IN RECENT YEARS

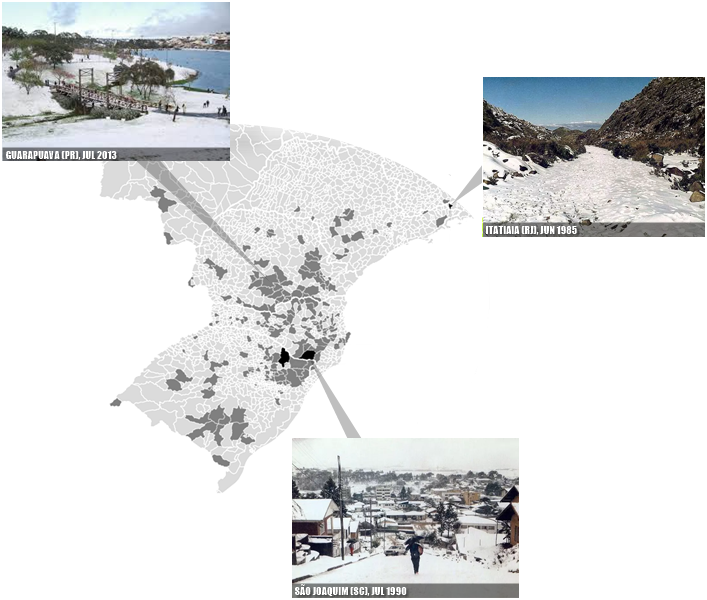

SNOW

Snow in Brazil often happens in winter in the mountains of Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, and Paraná, and is rarer at lower elevations. It is possible, but very rare, in the states of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais, and Mato Grosso do Sul. The greatest snowfall recorded in the country occurred in Vacaria on 7 August 1879, when more than 2m of snow accumulated on the ground. Other significant snowfalls where more than 1m of snow accumulated happened on 20 July 1957 in São Joaquim and 15 June 1985, in Pico das Agulhas Negras. São Joaquim has the most snowy days of any settlement in Brazil. Snow has been recorded in Curitiba during several years, but has not accumulated significantly since 1975. In 2013, snow hit several municipalities, including Curitiba. Snow has also occurred in Porto Alegre, but is very rare (Wikipedia).

HISTORICAL RECORDS OF SNOW IN BRAZIL SINCE 1879, HIGHLIGHTING 1M-OR-HIGHER SNOW ACCUMULER CITIES IN DARK GRAY (REDDIT)

ATMOSPHERIC DYNAMICS

Because the South Atlantic basin is generally not a favorable environment for their development, Brazil has only rarely experienced tropical cyclones. The country's coastal population centers are considered less burdened with the need to prepare for cyclones, as are cities at similar latitudes in the USA and Asia. In 2011, the Brazilian Navy Hydrographic Center started assigning official names to tropical and subtropical cyclones that develop within its area of responsibility, which is to the west of 20°W, when they have gained sustained wind speeds of 65 km/h and over. Hurricane Catarina is the first and only South Atlantic tropical cyclone to have reached hurricane strength, and impacted Santa Catarina as a Category 2 storm in March 28, 2004. It reached sustained wind speeds of 155 km/h and a pressure of 972 millibars. The hurricane damaged shipyards and several crop fields, and poorer people were affected the most. At least 2,000 people became homeless as a result of the storm (Wikipedia).

HISTORIC SERIES OF HURRICANES, IMAGE AND WAY OF OF CATARINA HURRICANE, UNIQUE IN RECENT HISTORY OF BRAZIL

Regarding tornadoes, southeastern South America has one of the most active corridors on the planet, spanning mainly N Argentina, S Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay. This zone concentrates severe supercells formed by the clash between warm, humid air and colder air descending from the Andes and higher latitudes, being one of the most dynamic and violent meteorological environments in the Southern Hemisphere — the USA is the world leader in recorded tornadoes — averaging about 1,225 per year (G1). Almeida (IC/UEPG, 2023) lists records of tornadoes from 1978 to 2018 indicate 581 events in Brazil, spread across 422 municipalities, 159 of which reported more than one occurrence — the southern states dominate overwhelmingly (411): Rio Grande do Sul (180), Santa Catarina (142), and Paraná (89). Outside the South, the states with the highest counts are São Paulo (89) and Minas Gerais (11). Beyond this group, occurrences are scarce and many records are imprecise, with the Central-West, North, and Northeast regions each reporting fewer than 30 cases. The deadliest tornado in Brazil struck the cities of Palmas (Paraná) and Canoinhas (Santa Catarina) on August 14, 1959, resulting in approximately 90 deaths (Gazeta do Povo). Twenty-five of Brazil's 26 states have recorded at least one tornado since 1970, the only one without confirmation being the state of Acre (Wikipedia).

BLACK HOT MAP OF TORNADOES IN BRAZIL, AND SOME HISTORICAL TORNADO RECORDS

'Flying rivers' are air currents that bring water vapour from Amazonia, in the equatorial zone of Northern South America, down as far south as Northern Argentina. The humidity carried by these 'airborne rivers' is responsible for much of the rain that falls in the WC, SE and S regions of Brazil. Amazing as it might seem, the quantity of water transported by the flying rivers could well be equivalent to or even greater than the flow of the mighty Amazon itself. Total amount of water released into the atmosphere every day by the rainforest at around 20 B tonnes. This compares interestingly with the total volume of water discharged daily (at a rate of 200,000 m³/s) into the Atlantic by the Amazon River: 17 B tonnes (Expedição Rios Voadores).

FLYING RIVERS' IN SOUTH AMERICA BETWEEN DECEMBER AND JANUARY

A dust storm, also called a sandstorm, is a meteorological phenomenon common in arid and semi-arid regions. Dust storms arise when a gust front or other strong wind blows loose sand and dirt from a dry surface. Fine particles are transported by saltation and suspension, a process that moves soil from one place and deposits it in another (Wikipedia). Although Brazil is not an arid country, dust storms have been recorded more frequently in recent decades. The phenomenon intensified especially after the severe drought of 2022, when large areas of São Paulo, Mato Grosso do Sul, and Minas Gerais were affected. Cities such as Três Lagos (MS, Oct 2021, Último Segundo), Morro Agudo (SP, Oct 21, Climatempo), Ribeirão Preto (SP, Sept 2021, YT) and Franca (SP, Sept 2021, YT), were among those impacted by these storms.

SOME SAND STORMS IN BRAZIL (Morro Agudo (SP, Oct 21, SEE) | Três Lagos (MS), Oct 21, SEE| Franca (SP), Set 21, VIDEO)

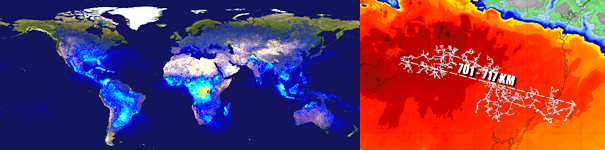

Massive dust emitted from Sahara desert (Sahara/Amazonia sand winds) is carried by trade winds across the tropical Atlantic Ocean, reaching the Amazon Rainforest and Caribbean Sea. On a basis of the 8-year average, 179M t of dust leaves the coast of North Africa and is transported across Atlantic Ocean, of which 102, 20, and 28 Tg of dust is deposited into the tropical Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Amazon Rainforest, respectively. The 28M t of dust provides about 22K t of phosphorus to Amazon Rainforest yearly that replenishes the leak of this plant-essential nutrient by rains and flooding, suggesting an important role of Saharan dust in maintaining the productivity of Amazon rainforest on timescales of decades or centuries (Yu, H. et al., American Geophysical Union, 2015).